Motorcycle Trip Planning pt 1: The Basics

When going on an adventure, determining what is the adequate level of planning is the subject of much debate. For a long time I was on the “no plan is best plan” side of that debate, however the lead-up to my unfortunate aborted experience trying to cross the middle east has forced me to actually try more in depth planning for safety reasons. The extensive planning gave me a new appreciation for the value of planning any trip, no matter the length.

To communicate my approach to making trip plans, I will be putting out a few posts in this series to underlines my philosophy while planning, and the tools I use to make my trips easier.

Objectives of this guide

To prevent mission creep in the planning phase that would suck the fun out of exploring, it’s important to define what we want to achieve. This is what I am looking to get out of a planning a trip:

- Layout points of interest (POI), including points of origin and destination in a way that enhances your ability to navigate through your trip

- Gain familiarity with the general outline of the trip and acquire the confidence necessary to deviate from plans

- Provide pre-programmed optionality when faced with unforeseen circumstances, from road closure to catastrophic equipment failure or health conditions

- Produce trip documentation that is usable and intelligible to yourself, and potentially anybody else in case of emergency

All of this will be done with very basic, publicly accessible and free tools, mostly Google Earth.

Notice how none of the parts above has to do with meticulously planning stops and producing comprehensive documentation of every turn. It’s about laying out enough things on paper that you can intelligently make decisions about your whereabouts without having to rely on the rigid instructions of your electronic aids at any point.

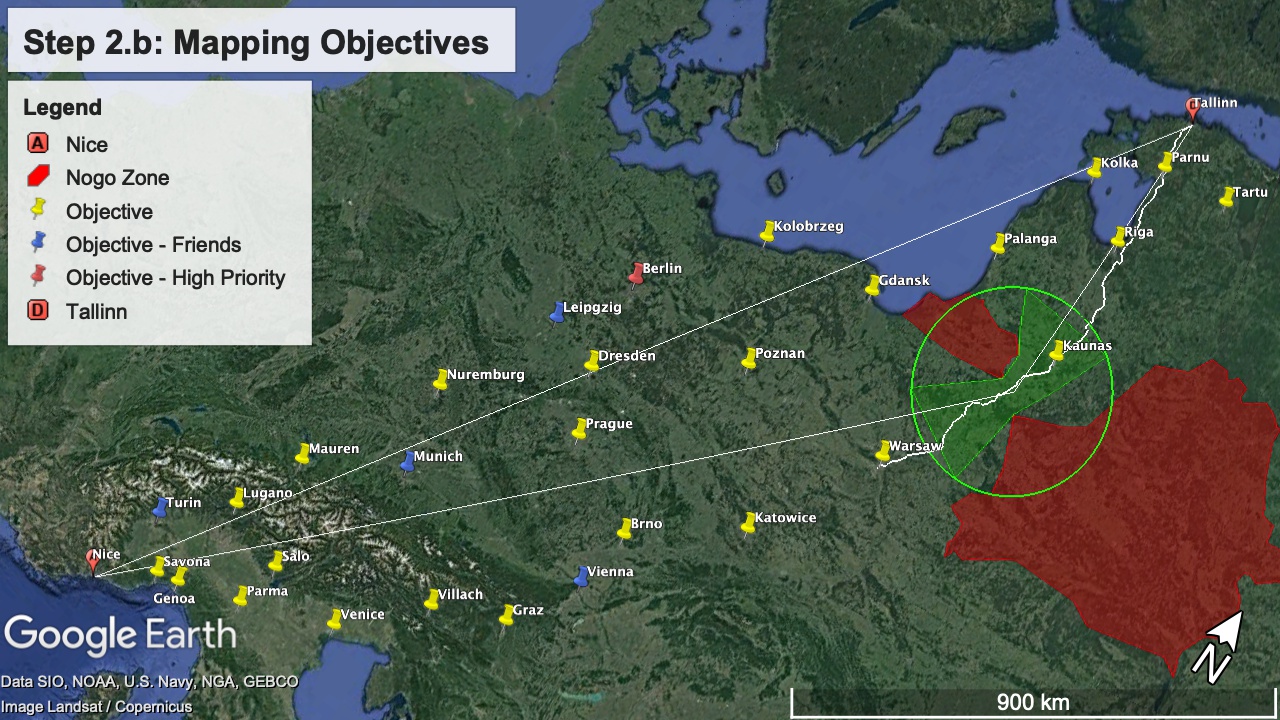

We’ll be following this general process:

Step 0: Determine constraints

The first step in planning any trip is determining the constraints that you have to work with. Unless you are an old-money millionaire and can afford to gallivant about aimlessly for however long, your hardest constraints will probably be related to time and budget. Time is directly correlated to the distance you can cover. Budget is generally correlated to where you can stop to rest, eat or enjoy yourself.

Another set of relatively rigid constraints will relate to your equipment loadout, including both your bike and the equipment your intend to carry. Your bike has a maintenance schedule, and a fixed fuel capacity, hence max distance between fuel and maintenance stops. Similarly, you as a rider also have fuel and maintenance stops, in the form of food breaks and rest, both overnight and while on the road.

A more variable category of constraints, let’s call them punctual constraints, are broader incidents which may or may not have an impact on your trip. This may include weather events, road condition or closure, and any fortuitous or unfortuitous delays. By their nature they really cannot be predicted or avoided by planning, but thinking about such possibilities will help you elaborate options, should you encounter them.

It’s important to mention that the idea here is not only to avoid the worst, but also to give you a way to enjoy the spontaneous opportunities presented to you in your trip without messing up the rest of your plans. If you have a general idea of what being half a day late entails down the road, or where you could pick up the pace to catch up, it’s much less bothersome to stay in a place a bit off your path with a newfound friend.

Here’s a matrix that sums up our constraints. The list is in no way exhaustive, I welcome any useful additions (submit a PR on my blog’s Github repo).

|----------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| | Nature of constraint |

|----------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Type of constraint | Gear | Rider |

|----------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Material | * Fuel range | * Total trip length (in days) |

| | * Maintenance schedule | * Frequency of rest stops |

| | * Road terrain | * Available / desired accommodation|

| | * Import requirements | * Visa availability / entry req. |

|----------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Punctual | * Breakdown | * Ill health |

| | * Road condition | * Weather conditions |

| |-------------------------------------------------------------|

| | * Bureaucratic mishaps |

| | * Ad-hoc opportunities and invitations |

|----------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

Material constraints should be clear before you leave. While I did not fully follow my own advice in my last middle east trip, I did due some basic points of due diligence during the break-in period of my Tenere, stuff like finding out what is maximum comfortable cruising speed, what is the fuel range to reserve and to empty, how long I could ride before needing a rest on both back roads and in town, etc. All my visas where also covered in advance for the entirety of my trip. Anything you forget to consider here is entirely on you… these material constraints, if not known, at least COULD have been known.

Step 1: Determine objectives

Unless your trip is an escape, you probably have at least some objectives, some theme. A few years back when I attended Mises Institute for in-person Mises U, I drove there in my car and took the opportunity to visit friends in Buffalo, NY and Akron, OH. Looking for a way to make this more fun, I made the theme of this trip “A Chicken Wing Pilgrimage”, and stopped by Atlanta, GA for some lemon-peppers. After this I stretched this definition a bit by going to Austin, TX for a month, because at the time I had relatively few time or budget constraints.

Here’s a non-exhaustive objectives you might set for yourself.

- People you want to visit

- Restaurants you want to eat at

- Tourist attractions you want to see

- Roads you want to ride

- Pictures you want to take

This is where I suggest you spend a significant part of your time planning. Having a lot of possible objectives is what will give you the choice of routes, and the choice of deviations from that route.

Step 2: Basic Mapping

This is where the planning part starts to become more concrete and visual. We’ll be firing up Google Earth and starting to make some lines on maps. Of course, this could also very well be done on paper maps and tracing paper or transparencies if you really want to go old-school.

I’ll give you a rough idea of how this step goes with a trip I am currently planning for next summer.

Step 2.a: Mapping constraints

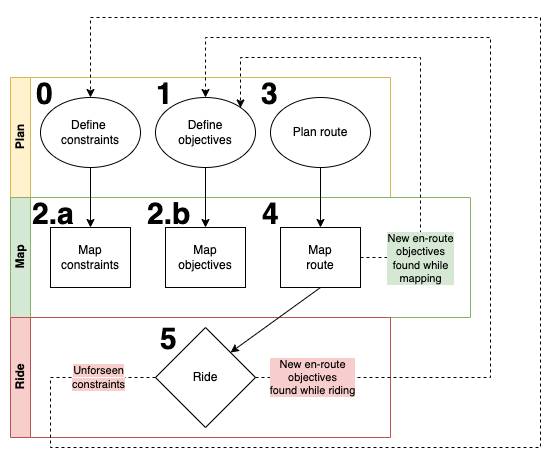

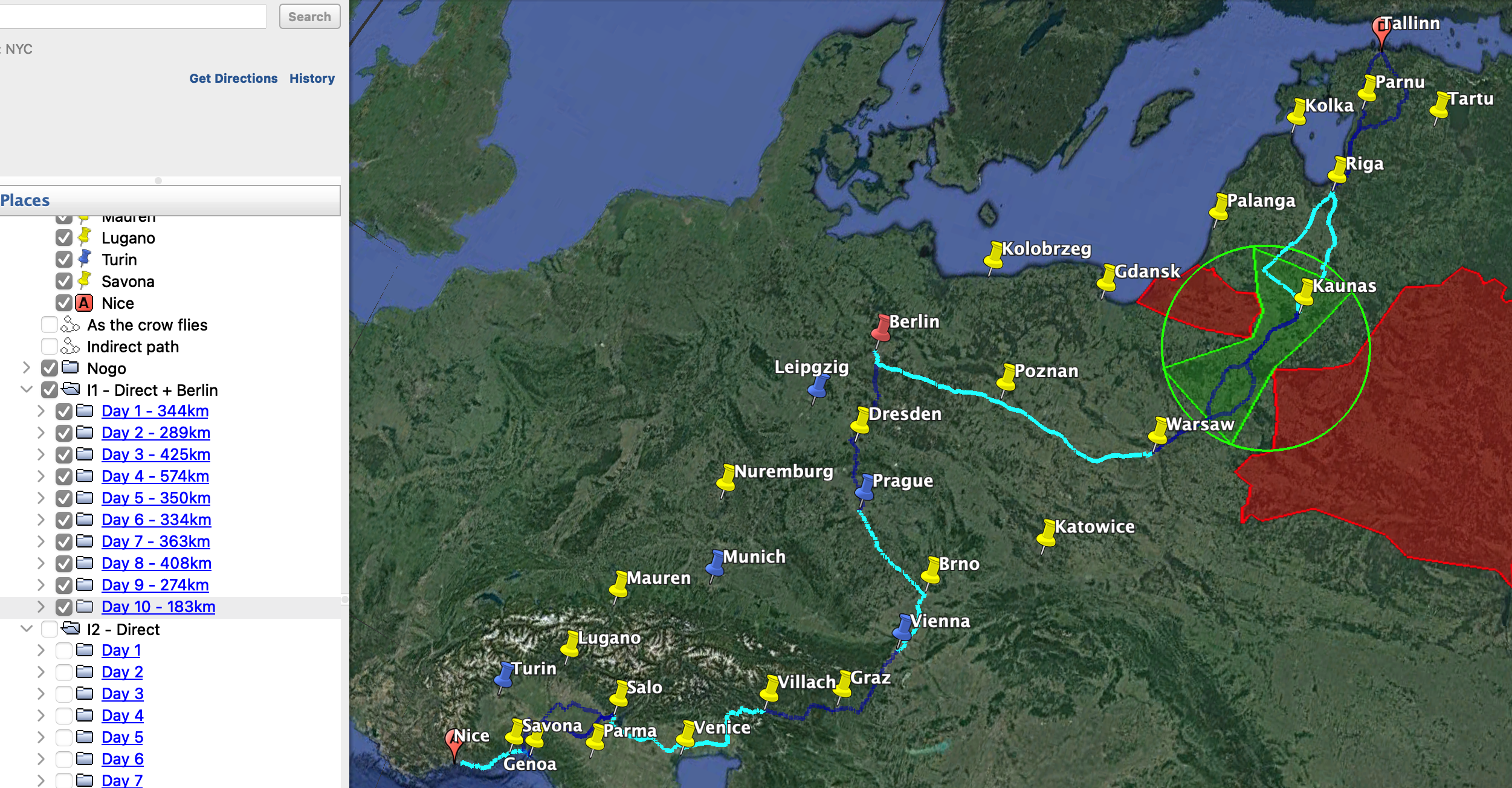

We map out constraints because it will give use a rough visual indication of what is possible and what is not. Generally, start with the hardest constraints first, and work your way through the easier ones. In my case, departure and arrival are not optional. Take a look at the first map.

Between my point of departure and arrival, the first, completely straight line represents the “ideal” path between two destinations, not taking into account the curvature of the earth. Still a useful tool to get a rough idea of what a path could look like.

Due to the travel documents I have and the current geopolitical situation, it’s not really worth it for me to try to get into Kaliningrad or Belarus; they are represented by the red shaded polygons. This restriction brings me to draw a more realistic direct path, the white line that is broken at the Lithuania-Poland border.

Another of my big constraints is the amount of vacation time I have available. I don’t plan to take more than 3 weeks to get from point A to point B… is this realistic? The white squiggly line is the shortest path between Tallinn and Nice; as pictured, it measures 2817km. This is the minimum distance I am going to cover, not accounting for running around at any destination cities or actually enjoying myself. Let’s crunch some numbers.

| Target Pace | Very fast (600km/day) | Normal (400km/day) | Leisurely (200km/day) |

| Hours riding at 50km/h | 12 | 8 | 4 |

| Hours riding at 100km/h | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| Days on the road | 4.695 | ~7 | ~14 |

| Delta to max | 16.305 | ~14 | ~7 |

Even at an extremely slow pace, I have a week’s worth of overhead! Completely realistic. My pace numbers here are derived from real world experience. On my Tenere (long wheelbase, heavy, stable, full fairings, etc) 600+km/day is within the realm of possibility.

On the bike I am planning to take on this trip, 600km a day WOULD probably be torture. I’m talking about a Husqvarna Svartpilen 401, an inherently smaller, less wind protected, more buzzy single cylinder bike.

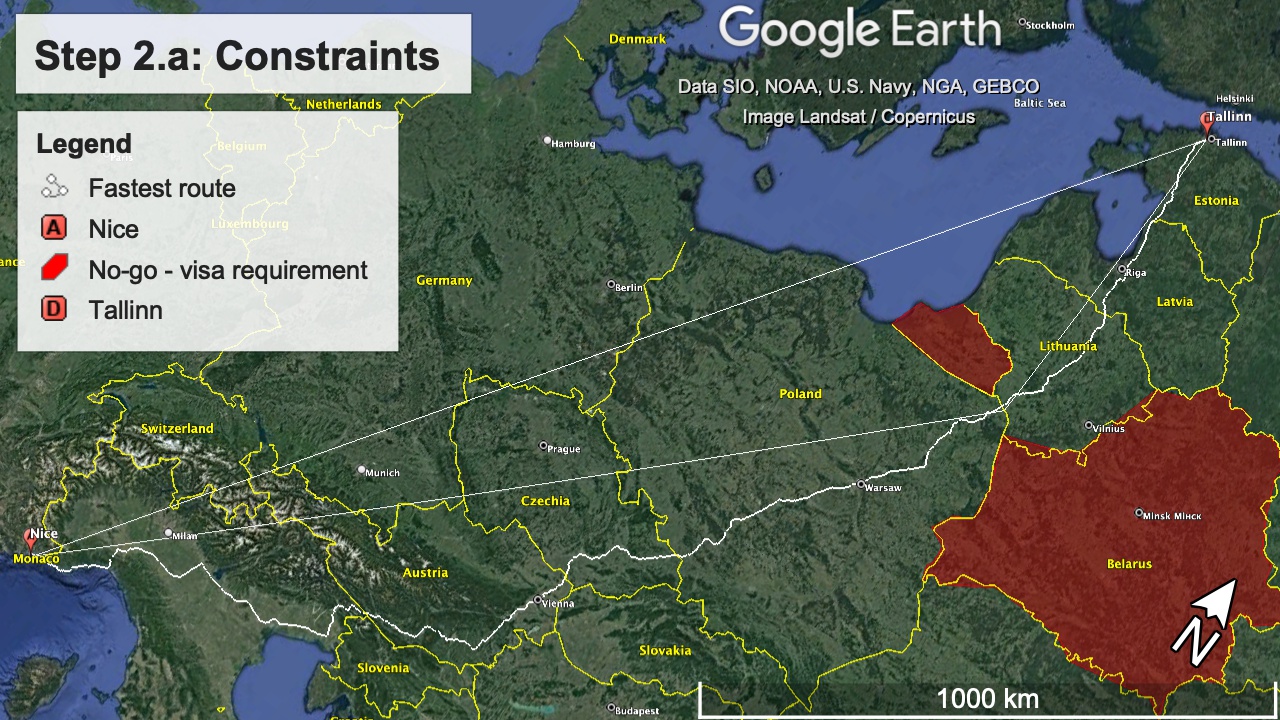

The bike is also going to be new, which means that it is going to need a break-in oil-change at around the 1000km mark. Despite the fact that I am going to do a hard break-in in Tallin on arrival (maybe 100km?), I still want to do another one at around the 1000km mark. Coincidentally, the shortest route from Tallinn to Warsaw is 982km on the shortest path… accounting for 25% of slack running around, this puts us just about at the Polish/Lithuanian border. Using a bit of artistic licence, we can draw a rough zone where I have to plan my oil change.

Of course, if we’re being honest I could do a 2 pint oil change pretty much anywhere… but I don’t necessarily want to. If possible, I would also want to have some sort of confirmation that I can get the filter wherever I decide to do it. For this reason I’ve decided to skip ahead and already add a waypoint in Kaunas, the largest city in Lithuania that more than likely has a Husqvarna dealer.

Step 2.b: Mapping objectives

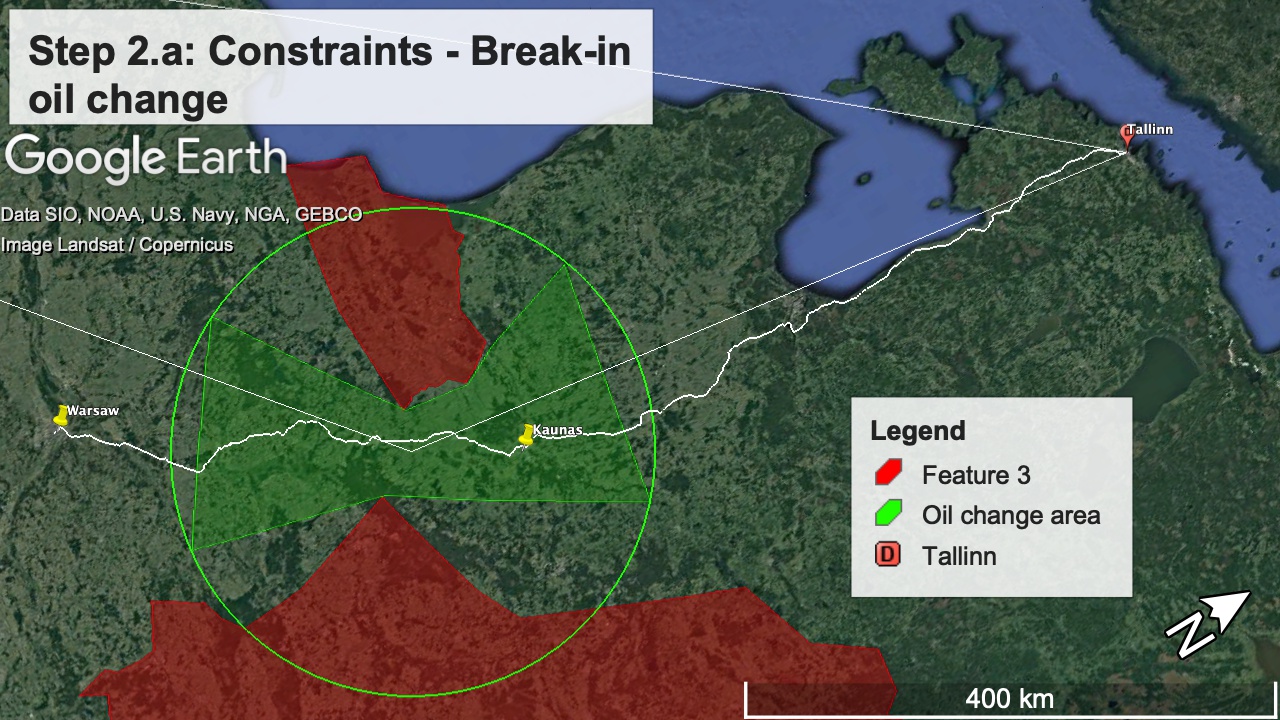

We can now start adding objectives. In my case, these are in the form of cities that I want to visit, either because I have friends there (blue), because I still haven’t been there (red), or because it’s convenient and probably interesting. The visual cues helps define our order or priority.

Here’s our map so far.

This is enough for the first cycle of route tracing, and then going back to previous steps to add, remove or refine our constraints.

Step 3: Plan route

With our potential stops laid out, we are ready to start drawing some paths. I use “plan route” instead of map route because at this point we’re really just using available tools, mostly the Google Earth routing tool figure out routes to see if this makes sense.

This is more of an art than a science; you’re designing something that sounds fun, has stops you want to visit, and respects your constraints. Where you have choke points, think about branching out.

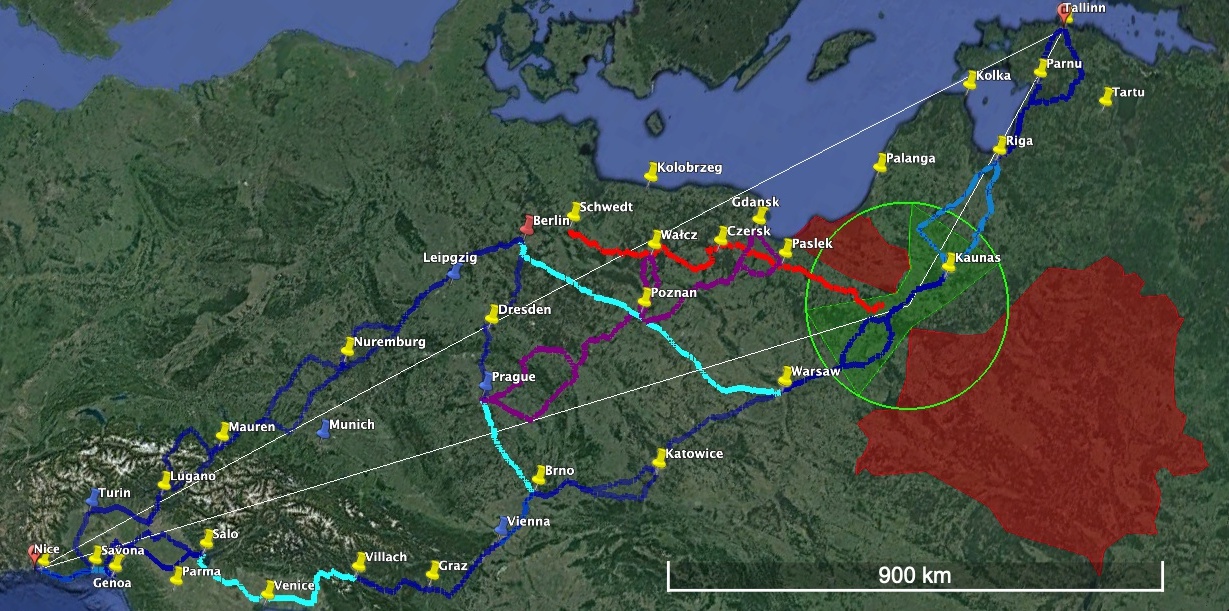

As you probably recall from 2.a, the most direct path between our departure and arrival points goes through Warsaw, Vienna, then north Italy… but I really want to go to Berlin! In this case, I’ll do a “German” route, by calculating shortest path between Berlin and Nice, then riffing on that.

This is suboptimal because I’ve done a lot of Germany and Switzerland already, and I’d much rather see Vienna. I also just remembered that I have a good friend that is around Prague most of the time… let’s adjust to reflect that.

Beautiful, although that detour through Berlin looks extremely long. It’s a good time to sanity check and make sure that we still fit into our constraints. This is where I usually try to find routes for the trip on a per-day basis, eyeballing what looks or feels like reasonable distance.

I am erring on the low side here because I really don’t want to be riding highway the whole way, and this is 100% of what these routes represent. In the next map, the days have been changed colours so as to make out different segments, and the lengths of the routes has been added to the folders containing them on the left.

With the distances as shown, we’re doing an average of 354km/day with the longest run being Warsaw to Berlin at a rather rough 574km of highway riding. If we cut this specific run in half with a stop in Poznan, we’re at 11 days, 322km/day, leaving us with 10 days of slack to do whatever we want with!

I also know from experience that the last two days could easily be condensed into one if they had too. This leaves us a lot of room to zoom in, and define routes that manually on interesting passages.

Step 4: Map the route

At this point, we could probably stop here and yolo it. Firstly, we have lots of slack with regards to time. Secondly, this is a trip through the eastern EU where we’re unlikely to encounter major setbacks that can’t be solved relatively quickly. We could most likely get away with putting our destinations into Google Maps on our phone every morning, highways and toll roads disabled, and follow the route. Our distance covered would likely increase by about 25%, our average speed would be lower, but we’d essentially be guarantee to find some cool stuff.

Any additional planning is really just refining the rough path that we already have, and maximizing whatever could happen in that trip. Since I have several months before departing, I’ll go ahead and map stuff out in detail anyways.

Since I’m using a scrambler bike for this trip, why not try it out on dirt? Some volunteers are already maintaining ready-made, very well annotated GPX files describing the Trans Euro Trail, and from the Youtube videos I could find most sections are relatively easy dirt and gravel roads that would be completely suitable for my bike. It’s probably not a good idea to try offroading before my break-in oil change is done, so let’s see what there is in Poland.

On the map above, the TET path in Poland relevant to me is in red. This is what I would call a properly mapped route, a turn-by-turn outline of the exact path you’re going to take, with annotated waypoints that include descriptions, warnings, etc. We really don’t need to put any more effort into this for my use case.

I’ve added a few stops along the way at shorter intervals since I obviously won’t be able to cover as much distance on dirty, and some escape paths (purple) from my planned stops in case the trails are too hairy to complete.

Step 5: Ride

Our full map now looks something like this.

What we have now is a perfectly actionable high level plan for a trip. What blanks need filling in can easily be filled in on the trip.

Next steps

To perfect this, we’d have to go through other cycles of defining and mapping out constraints and objectives on smaller portions of the trip; we’ll do this in the next posts, with increasingly sophisticated tools.

We’ll source data from various external sources, and get a bit tighter on the estimation of distances with isochrones and other cool open-source pieces of software.